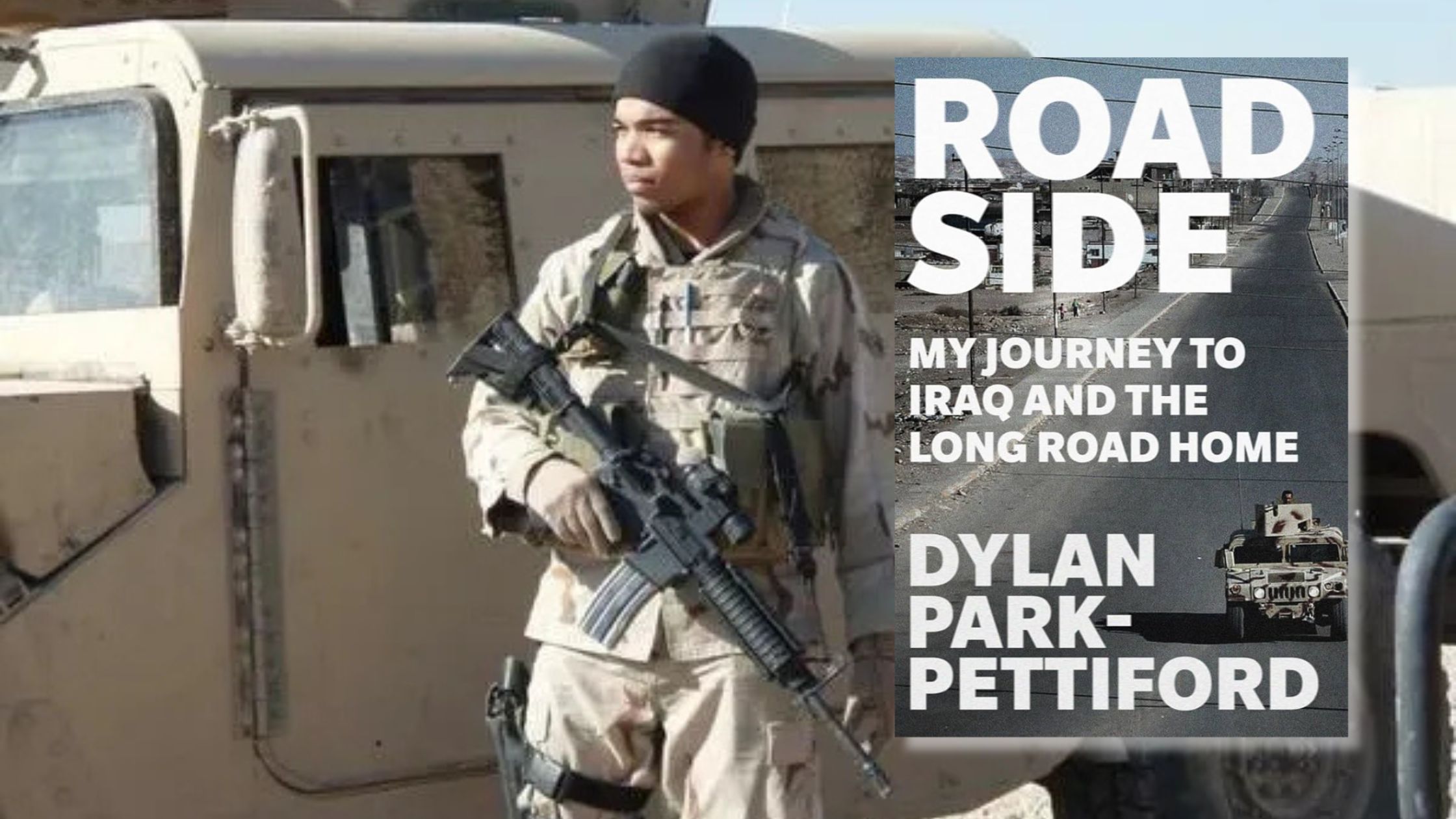

via Dylan Park-Pettiford

Let’s get the embarrassing part out of the way first.

Last January, hungover and hopeful, I made the same promise I make every year: I am going to become a Reader™. I vowed to crush 40 books. I was going to trade scrolling for David Foster Wallace. I was going to be the guy at the bar who casually says, “It’s actually quite Kafkaesque,” and means it. I’ve definitely been that kind of smug former English major douchebag before.

Fast forward to December, and my “Read” pile is pathetic. I didn’t read 40 books. I barely read five. My brain is smoother than a cue ball, polished to a shine by too many rage-inducing podcasts about how AI is destroying every creative endeavor ever. Then I open up my Instagram, and I’m sucked into an infinite wormhole of 15-second algorithmic slop that aligns all-too-perfectly with my interests. For example, currently, my feed is nothing but people with pet octopi and skiing videos. Sometimes I try to farm that sort of clout for myself, thinking that it’s “good for my career” when I probably should just put down the phone and write something.

But there was one exception. This book glued me to the couch.

It’s called Roadside: My Journey to Iraq and the Long Road Home by Dylan Park-Pettiford. It is hands-down the best thing I read this year. You can go buy it on Amazon or at your local bookstore.

If you don’t know Park-Pettiford, fix that. He’s an electric follow on Twitter and Threads. I actually first wrote about him on this site way back in 2017, when he went viral for sharing the incredible story of how Brahim—an Iraqi refugee—saved his life twice. That thread was a refreshing moment of humanity during the initial stupidity of the racist “Muslim Ban” news cycle. It’s stuck with me ever since.

It also helps that Park-Pettiford actually knows how to tell a story for a living. Since his time in the Air Force, he’s carved out a legit career in Hollywood, racking up writing credits on shows like the Bosch spinoff, All Rise, and Ron Howard’s 68 Whiskey. He’s written for Marvel. The guy went from military service in Iraq to film school at USC, and that pedigree does a lot of heavy lifting here. It’s written with the sharp pacing and dialogue of a show you’d binge in a weekend.

Roadside is his memoir about joining a U.S. Air Force Special Operations unit, but if you’re expecting a glistening, patriotic ode to American might where the hero never misses a shot, look elsewhere. This isn’t that.

This is a story about the absolute absurdity of the Global War on Terror era. It is wildly, darkly hilarious, and completely unvarnished. It captures the ominous vibe of that war: the whiplash between total boredom and sheer terror. One minute you’re pounding energy drinks, watching bootleg DVDs from the PX, and figuring out innovative ways of pleasuring oneself with Uncle Sam-issued night vision goggles; the next, the barracks are shaking from a roadside bomb.

I had a chance to speak with Park-Pettiford, and he was the first to admit that the public has “Iraq War fatigue.” He wasn’t interested in adding another cliché to the pile. “All the stories you could tell were told,” he said. “I’m not trying to paint myself as some war hero. My story is more along the lines of Pauly Shore In The Army Now… just this bumbling idiot who is in Iraq all of a sudden and did not belong there. I never actually pictured myself at war… and the next thing I know, I’m in the turret of a Humvee getting shot at.”

Park-Pettiford’s perspective is distinct. Seth Rogen apparently called him the “Black Lieutenant Dan” because his family has fought in every American conflict since the Revolution. But the absurdity peaks early: Park-Pettiford found out his maternal grandfather served in the North Korean army during a military background check while he was working at a coffee shop. He thought the Feds were there to bust him for his illegal Napster and LimeWire downloads. Nope. Just generational enemy-of-the-state stuff.

The heart of the book, though, is his relationship with a Kurdish teenager named Brahim. Back in 2017, when I covered what Park-Pettiford shared online about the reunion, it felt like a miraculous viral moment. It was an epic middle finger to the “Muslim Ban” rhetoric of the time. But Roadside offers the meat and potatoes of that story that a Twitter thread never could.

In Roadside, Park-Pettiford shares a deeply personal, flesh-and-blood evolution of two kids from opposite worlds just trying to survive. You see the risks Brahim took not as a plot point, but as a daily, terrifying reality. By the time you get to the famous coincidence involving a Phoenix taxicab later in the book (the moment that made the internet melt down years ago), it lands with an especially devastating weight. As the reader, you’re reminded that the universe works in weird ways. It leaves you with the lingering suspicion that the people we leave behind in the circus of our youth aren’t ever really gone; life just waits for the most improbable moment to loop them back in. It’s trippy to think about, but sometimes coincidence is just a pattern we haven’t recognized yet.

There is a specific scene early in the book that stopped me cold. It’s 2004. Park-Pettiford is in his hometown, staring at a memorial for Pat Tillman. He listens to Tillman’s brother speak, explicitly saying not to romanticize Pat’s death, that the war itself is what killed him.

via Dylan Park-Pettiford

And yet, in the ultimate irony of being a bored, lost 19-year-old, Park-Pettiford hears that anti-war message and decides… to enlist.

I’m the same age as Park-Pettiford. Reading that scene dragged me back to the specific, disorienting haze of growing up in George W. Bush’s America in rural Pennsylvania. I didn’t serve, and I’d be a fraud if I claimed to understand the combat experience. I’ve never experienced the hell of war. But I remember the vibe of the times. If you were a teenager in the mid-2000s, you lived in a bizarre split-screen reality. You had recruitment ads during NFL games that looked like Call of Duty and performative yellow ribbon magnets on every SUV, along with the pressure to “do something” in a conflict that felt increasingly confusing. Meanwhile, we were all coming home to watch Jon Stewart dismantle the administration’s talking points on The Daily Show, trying to reconcile the relentless patriotism with the confusing reality unfolding on CNN.

Park-Pettiford captures the fever dream of that era perfectly. He dissects the cynical rhetoric of the time: the war dog defense contractors getting rich while grunts got broken. Nothing captures this quite like the opening to the book’s third act, where Park-Pettiford quotes an Outback Steakhouse promotion as a sort of grim welcome home: “For your service to our great nation, we’re offering a free Bloomin’ Onion and any Coca-Cola beverage (with the purchase of an entree).” It’s a nice gesture from corporate America, sure, but the absurdity of a free Bloomin’ Onion acting as a salve for the horrors of war is stark. That parenthetical (with the purchase of an entree) is the perfect, accidental artifact of 2000s patriotism: loud, caloric, and entirely transactional. It captures a specific frequency of absurdity that calls back to the best war art of the era. It feels like a spiritual successor to Generation Kill, sitting right alongside Evan Wright’s reporting and the HBO adaptation in the canon of GWOT surrealism.

He doesn’t shy away from what happened after the deployment, either. The “Long Road Home” subtitle lives up to its promise, detailing the substance abuse, the divorce, and the homelessness that followed with brutal clarity. Perhaps the most heartbreaking thread is the loss of his younger brother to gun violence, a tragedy that underscores the violence he faced both abroad and at home.

What makes Roadside land so hard is Dylan’s sincerity. He holds a mirror up to his own life—failed relationships, traumas, and all—with a level of honesty that most of us would find terrifying. When we spoke, he admitted that this unfiltered approach even rattled his own mother. “She was like, ‘Why are you so disgusting?'” he laughed. “But I wrote the book that I would want to read. I wasn’t trying to sound like Ernest Hemingway. I just spoke my voice and my truth.”

That truth has drawn a mixed bag of reactions. Park-Pettiford told me he’s gotten some confused emails from the ultra-serious special operator crowd—think, Navy SEAL types asking, “What the !@$ did I just read?” because he openly admits to being a “screw up” rather than a commando. But for the guys he actually served with, the reception has been vindicating. “They were like, ‘Dude, we didn’t realize how stupid it was when we were out there,'” he said. “‘But you putting it into words summed it up perfectly.'”

Park-Pettiford tells his story with a specific wit that will make any millennial currently staring down a mid-life crisis smile in recognition. He anchors the heavy stuff with the specific cultural touchstones of our youth: the anxiety of illegal LimeWire downloads we all participated in; the way the Golden State Warriors were a shared bond for him and his late brother; and how hip-hop and heavy metal music became the unlikely bridge connecting him to Brahim in Iraq. Even the chapter titles play like a scorched CD-R from the mid-2000s, with nods to Third Eye Blind (“Semi-Charmed Life”) and a particularly powerful chapter titled “The New National Anthem.” It references Strata’s 2007 anti-war anthem from their album The End of the World—a track with lyrics about “corporate-sponsored war” and “recruiting my little brother” that feel like they were written for this exact story.

Roadside doesn’t romanticize the uniform. It doesn’t treat the military like a sacred cow for personal growth, nor does it treat it like a cartoon villain. It treats service as a deeply complex life stage—a formative chapter that permanently alters your worldview, filtering every subsequent experience through the lens of what happened in the desert. To me, a civilian, his service was incredibly valiant—reading this, you realize it took massive stones to do what he did. I’ve always deeply admired that call to service, especially when I weigh it against my own reality at the time: I was beer-bonging lukewarm Milwaukee’s Best in a sticky college basement while he was deployed in Iraq. But you also get the distinct vibe that the rote phrase “Thank you for your service” rings hollow to someone like Park-Pettiford, carrying far less weight than a simple, bewildered: “What the hell were we even doing over there?”

It treats the war as the inescapable background radiation of our youth. It preserves the granular history of a Millennial conflict that feels like it’s being scrubbed from the timeline in real-time. In my opinion, for those of us who watched planes slam into the Twin Towers on TVs in a high school classroom, it validates an anger and generational angst that deepens with age—the realization that so many peers were fed into a machine where the answer to “for what?” is just a shrug and the grinding acceptance of American imperialism.

We can’t let history forget these soldiers and their experience. Screw that.

Ultimately, Roadside is a triumph in navigating a world that is existentially confusing. By weaving together the improbable survival of Brahim with the tragic loss of his own brother back home, Park-Pettiford shows us that upheaval is life’s only constant. Yet, he writes about this absurdity with such raw, unpretentious honesty that it becomes a sort of survival guide. He waded through some circles of personal Hell to get here—war, addiction, grief—and the fact that he’s still standing and thriving offers a blueprint for anyone else trying to crawl out of their own trenches.

In that way, his story is so deeply human. The politics might not make sense, and the losses never make sense, but the people we cling to are pretty freakin’ important.

So, yeah. I failed my reading goal. I am not a scholar. Wah-wah. But I read Roadside, and honestly, I’m really damn glad that I did.

That’s enough. Go buy it.

Note: If you enjoyed this review, subscribe to my Substack, The Wenerd Weekly, for more thoughts on 15+ years of BroBible, books, culture, and my ongoing battle against algorithmic brain rot.