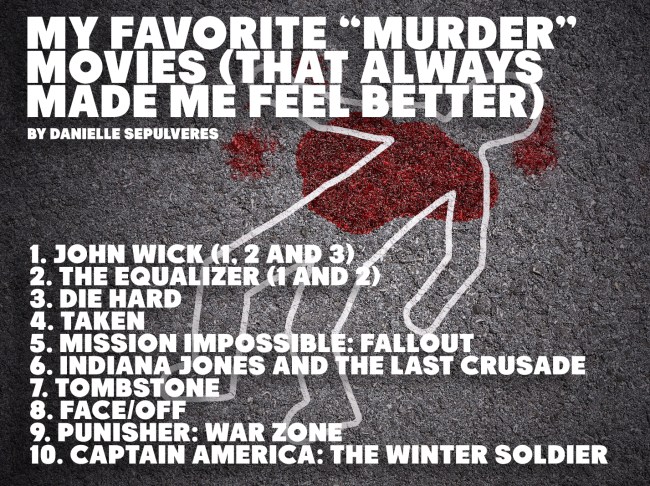

John Wick: Chapter 2 | Summit Entertainment

One hundred and sixty-seven.

That’s the body count in “John Wick: Chapter 3.”

If you think that’s a spoiler, go swallow a spoonful of cinnamon.

In all three movies, each death at John Wick’s hand invigorates me, fills me with a sense of calm that justice is being served, that for two hours, death itself isn’t actually real, just a spectacle to view, to entertain and to even root for in all it’s hideous gory beauty.

Someone who has been wronged is avenging that wrong a thousand times over, and it feels excessive but oh so RIGHT.

There’s a scene in “Catch and Release” (a pitiful death toll of one person in that movie) where Jennifer Garner’s character is having epiphanies about herself after discovering her fiancé’s infidelity and secret child (that’s a spoiler sorry) and announces “I love natural disasters! I want people to die in them! I am genuinely disappointed when the death toll is low.”

Besides the fact that Timothy Olyphant completely falls in love with her in that scene, I also relate to her sentiment since that is how I feel about action/thriller movies and television shows.

But I’ve realized that it goes a little deeper for me.

The escapism of massive death delivered so outrageously like a mad queen on a CGI dragon laying siege to an entire city is what I crave when grief in real life has gripped my heart so hard some days it’s hard to breathe.

It’s been a while since I’ve been able to find a therapist who takes my insurance, so when I wanted to understand the psychology behind why this over the top violence acts as such a balm.

I very scientifically asked my cousin who just graduated with her PsyD if there was a genuine reason for how I could find fictional death uplifting when actual death was tearing apart my insides.

“There’s a control factor,” she explained. “It’s controlled and on your terms, similar to women liking true crime. Also, the fact that you know it’s not real.”

So basically the way that my real feelings of grief are typically caused by circumstances out of my control, choosing to watch these films and shows is my way of restoring a semblance of balance in a sometimes chaotic world.

I also checked in with grief expert Dr. M. Katherine Shear of The Center for Complicated Grief at Columbia to discuss whether this was even remotely a healthy way to be processing my emotions.

After telling me that she was fascinated by my email explaining how these movies help me, she suggested that films and shows where righteous vengeance is sought provide me with an alternative world where things can go right instead of wrong.

And that what I’m experiencing could also be connected to terror management theory and mortality salience.

“When anybody in any way confronts the concept of death or mortality, they have documented that it activates certain areas of the brain that are associated with anxiety, but a unique area that has to do with self-annihilation. In experiments where they trigger mortality salience, it’s found that it increases the desire to be part of a larger group,” she explains.

And while this is something that can negatively lead to the rise of prejudices or feelings of superiority, in my particular case, it seems that I instead simply crave the connection of fandom and of being able to discuss the movie or show with others who have seen it.

Or to be in a darkened theater surrounded by other people also enjoying Keanu Reeves and Denzel Washington righting wrongs and finding satisfaction in vengeance.

Considering my first feeling after exiting the theater is usually about who I can text or call to rehash it, this feels accurate.

Grief has been an unwelcome constant in my life.

I attended my first wake at the age of six. Not at all understanding why everyone was so sad and confused why a woman seemed to weirdly be on display sleeping in a shiny wooden box like some kind of gray-haired Sleeping Beauty.

I wouldn’t attend another one until I was a teenager when my raging hormone mood swings coupled with a severe lack of maturity in how to express sadness and anger made for a volatile unhealthy combination.

But in my twenties, when I devastatingly lost friends my own age, I should have finally realized that maybe no one ever really knows how to grieve or how to communicate well about it.

I think we get thrown platitudes most of our lives about time healing wounds and people being in a better place instead of actually addressing the pain it all causes.

The idea that the pain might never go away is maybe just too terrifying a concept to say out loud.

There’s no comfort in acknowledging that you will never feel completely whole again, because the draw of feeling better one day is so much more enticing, so much better to cling to when you’ve lost someone and feel like you’ve completely splintered apart without them.

So we just learn to find comfort in small moments, even unlikely places like the John Wick universe.

Dr. Shear tells me, “Loss typically evokes a whole range of complex feelings. You miss people because of how much you love them, our animals too, we love our animals. We say that grief is the form love takes when someone we love dies. It’s all those big complex feelings, we don’t necessarily focus on them when the person or animal is alive.”

Once a beloved person or pet is gone, those emotions get displaced, and now there’s a whole big mess of feelings that are difficult to manage.

That’s why these movies offer distraction and satisfaction.

My messier angry emotions feel somewhat quelled when Denzel Washington’s Robert McCall cares to defend people who can’t defend themselves to hold the guilty parties responsible for the death of his best friend.

John Wick not only represents solidarity in losing the love of your life but also the devastation of losing your dog. (I know I know, he wasn’t “just” a dog).

Dr. Shear says suffering is part of being human, “grief emerges naturally after we lose someone and finds a place in our life. It needs a place.” In the third installment of John Wick, he’s asked why he wants to live, and he says, “my wife, Helen. To remember her. To remember us.”

So if John Wick and Robert McCall can find a place for their grief to reside, maybe I keep watching because I’m still looking for a place for mine.

Just ideally through more pacifistic means.

Danielle is a freelance writer contributing to The Washington Post, NY Mag, SELF, Cosmopolitan, and various other places. You can follow her on twitter @ellesep.