Getty Image

Last week, Kobe died. For some reason, it affected me more than 9/11, more than the deaths of my grandparents, more than the deaths of multiple family dogs. Those aren’t jokes; those are simply the biggest tragedies that I have as reference points from my life. I felt completely confused, shaken, angry… hitting all the stages of grief for a guy I never knew.

Every time I saw a clip of Doc Rivers or Shaq weeping, it felt like the wound was cut fresh. I was sad, and then sad about how sad I was, which made me more sad.

Psychologists talk about layers of grief—something I didn’t understand until this. In a way, I feel lucky that I’m not religious because this would have been very tough to square with a belief in God. It was senseless, absurd, and seemed possible only in a universe devoid of some divine force that would, surely, have protected that helicopter and those it carried.

I revered Kobe. Loved him, admired him, studied him, tried to move like him—all the platitudes we’ve heard about the man were things I’d felt of him since I was a boy. I know these aren’t new revelations: everyone seemed to feel this way. But it’s important to know that before I get to Ari Shaffir.

When the news broke about Kobe, it was jumbled, messy, and in some cases, completely wrong. I read that Rick Fox was on the helicopter. Then I heard that only Kobe and the pilot were aboard. And then, in the worst twist of all, I read that none of Kobe’s daughters were aboard only to learn hours later that young Gianna Bryant had perished alongside her father.

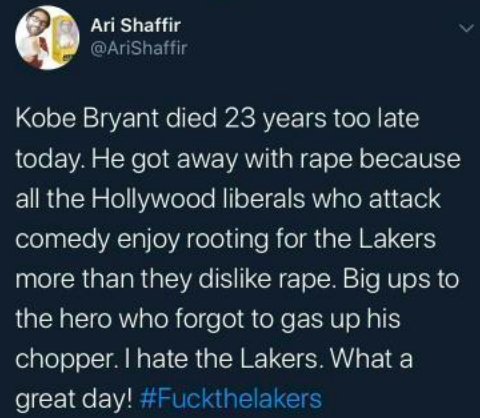

It was during this bewildering, tangled torrent of true and false news alerts that comedian Ari Shaffir took to twitter and instagram. He tweeted the following:

Then he doubled down with this video on Instagram:

https://twitter.com/Ovrnundr/status/1222068472533962752

Fans of Ari might have recognized a familiar, incendiary slant: poke the bear as it mourns a beloved icon. Ari would later explain that he always writes something terrible when a celebrity dies.

https://www.instagram.com/p/B73EHlTFrBy/

Still, for those new to his work, this introduction was a baptism by hellfire. The tweet and the video exploded (he has since taken them down).

Now before I proceed, a two-part disclaimer: first, I’ve met Ari a couple times, but only in passing as we waited in a hallway for our spots on the lineup. I enjoy his comedy and make a point to watch as he works out new material.

Part two: six months ago, I was fired very publicly from my job at Barstool Sports for writing a blog about a young woman in Utah who had gone missing. In the blog, I made light of the fact that she was a proud and active sugar daddy dating website frequenter. As I read the various articles about her case, I saw that her sorority sisters had reported that her Instagram account was liking photos, and they (and I) took this to be a hopeful sign that she was alive. It was a slow news day—the Friday right before the 4th of July—and I was struggling to find stories to blog. The expectation at Barstool was that we would write 3-4 blogs a day, and the sugar daddy thing, coupled with the positive development from her Instagram activity, were enough to send me typing.

Most people wouldn’t have touched a missing persons case with a ten-foot pole, but after two and a half years at Barstool and over 1,500 blogs, I suppose my judgment took a day off. Tragically, just a few hours after I wrote the blog, she was discovered murdered. From that vantage point, my blog took on a far more sinister hue, and I was fired for it. You can read more about it by googling my name. Trust me, it was covered.

I note this because I may be somewhat biased from my own experience. Of course, what I did differed from what Ari did in some key ways: I didn’t know the girl was going to be found dead when I wrote about her, nor was she one of the most beloved athletes of all time. But when it comes to a comedian making inappropriate jokes about a publicized death, inciting the ire of the internet, and losing work over it, I’m… familiar.

In the week since Ari punted the hornet’s nest, two distinct camps have formed. In one corner, you have Kobe diehards threatening to hurt Ari. Some of them are calling in bomb threats to comedy clubs where he is scheduled to perform; some are posting his address and encouraging people to find him, effectively placing a bounty on his head. They say things like “I can’t wait for you to get to Philly/Portland/Chicago/LA” and “You’re going to get what’s coming to you.”

Allegedly, they posted the addresses of his family members to enact some kind of peripheral vengeance for Kobe. In search of a palliative for their grief, they found a diversion in Ari Shaffir who—perhaps unwittingly, perhaps intentionally—painted a target on his chest as if to say come and get me.

If you come to Philly we’re taking care of you on site. There won’t be any talking or negotiating. On fucking site. Don’t book shit here, don’t step foot in the city we’ll handle you accordingly.

— Zamboni (@Ghost_Of_Phife) January 28, 2020

If I ever catch Ari, it's on sight. No joke. I might really hurt that dude

— Anthony Stewart (@ItsAntDoe) January 28, 2020

Someone find his family members and stop them out please

— Dee Hall (@therealdhall100) January 28, 2020

https://twitter.com/enginesucked/status/1221760474263539713

In the other corner stand the Ari Shaffir supporters: comedians, fans, and friends who write this off to “Ari being Ari.” Some say that anything goes in the name (and pursuit) of comedy. Free speech is an American right, and that means we should not be made to fear for our safety based on the things we say.

As comedians feel the walls of PC culture closing in, we have pushed back to preserve our space. And sometimes, our push takes the form of jokes (or otherwise) that go too far. But by whose standards? Who draws the censorial line? For many comics, that demarcation of our acceptable operating space serves as an invitation—call it a dare, even—to not just tiptoe along its borders, but to barrel through it with unapologetic aplomb. Ari has made a wildly successful career doing this. He recently made news for “dosing” Bert Kreischer with MDMA in Bert’s home (slipping the drug in his drink without Bert’s knowledge)—a revelation made on Rogan that angered everyone in the room, cementing him as a heel even among his close friends. Ari’s Netflix specials hit for the cycle of polarizing topics: rape, abortion, race, religion. And to many (myself included), the specials were terrific. Why, then, would he ever think to ask himself “is this too much, too soon, too far?”

And finally, there are those of us in the middle, wondering why the hell the ring is on fire. Non-comedians admit that Ari’s words were deeply insensitive, but that they should hardly elicit some street fatwa against him.

The comedians here don’t want to piss people off with our jokes, but we want our comedian friends to like us, to see us as one of their own. Jim Gaffigan, Kevin Hart, and Ellen Degeneres, great as they are, are rarely cited as your favorite comic’s favorite comics. That rarified air is bestowed upon the likes of George Carlin, Richard Pryor, Joan Rivers, Dave Chappelle, Dave Attell, Jessy Kirson, Patrice O’Neal—wrecking balls who razed any and all structures of confinement to repave the road their way. Yet those of us in the middle can’t afford to alienate crowd members because, let’s be honest, it’s not like we have audience members to spare.

In the end, I was struck by this thought: do you really think that Kobe would have wanted people to hunt down a comedian for dragging his name? Here was a man who loved nothing more than silencing his haters with a dominant performance: he loved playing in hostile arenas on the road. The louder the boos, the better he seemed to play. Never once did he retaliate against those who cited his rape case to denigrate his character, or who said he took too many shots, or who called him overrated, overpaid, and a diva when he couldn’t get along with Shaq. Nor did he call upon his fans to fight those who sought to tear him down.

Instead, he rose above the fray, and this ultimately won over even his most stubborn detractors. Eventually, we all drank the Kobe Kool-Aid. We couldn’t beat him, so we joined him.

I struggle to imagine a scenario where Kobe Bryant would approve of these violent designs. I suspect he would say, simply, to let it go. Haters gonna hate, Lakers gonna… lake?

And Ari gonna Ari.