Getty Image

As Hollywood continues to delve deeper into an age of endless IP and franchise filmmaking, the art of becoming and remaining a unique director is becoming increasingly difficult.

Take Chloe Zhao, for example: Eternals — the wildly heady sci-fi epic that served as the director’s follow-up to the Oscar-winning Nomadland — currently has a 62% critic score, a number that represents both the lowest in the Marvel Cinematic Universe and her filmography at large. Zhao tried to, and succeeded in, bringing her own sensibilities to a wider audience, and the very critics who’ve spent years praising her are now largely rejecting her Marvel film for those very same things. Regardless of who you are, whether justified or not, making your creative eccentricities mainstream remains a difficult task. Unless, of course, you’re a filmmaker like Edgar Wright, who has someone made his originality his own personal IP.

When you see an Edgar Wright film, you simultaneously know what to expect while also never seeing it coming. That was true when he burst onto the scene with the delightfully irreverent Shaun of the Dead and it remains true to this day with his latest project, Last Night In Soho. In a Hollywood landscape that’s increasingly reliant on the ideas of others, Wright continues to tell his own stories. Here’s how he does it.

Introductions

BroBible (Eric Italiano): Folks, today I am thrilled to be chatting to this guest of ours, you know him as the director of films such as Shaun of the Dead, Baby Driver, Scott Pilgrim vs. the World, and his newest film, Last Night In Soho, which will be hitting theaters on October 29th. Ladies and gentlemen, it is Edgar Wright. How are you today my man?

Edgar Wright: I’m good, thanks for having me.

Love for the horror genre

BB: Absolutely. First of all, congrats on Last Night In Soho, I really enjoyed it, just like I seem to do with all your work. But before we talk about the film itself, I want to talk about its genre. What does horror mean to you and is it always something that you planned on experimenting in?

EW: It’s always been something that has excited me even before my first experiences with horror movies, with them being something illicit that I couldn’t see. My parents used to buy me and my brother this magazine in the U.K. called Starburst, which was like a cross between Starlog and Fangoria. And it was mostly around the time of the Star Wars movies, the original trilogy, and when I was about seven, my parents bought me this magazine, but I’m not sure they ever really looked at the content because there was a lot of stuff about horror films in there.

I just remember as a seven-year-old reading about Lucio Fulci zombie films and slasher movies and ‘American Werewolf in London’, ‘The Thing’, knowing full-well that I could not see any of these movies. And in some cases, I wouldn’t see the movies for another five years or more. Sometimes even 10 years. So it is something where I was always very interested in the genre, even before I’d seen some of the movies, and I guess it’s just something about the horror genre that it’s at its best when it is something that’s disturbing to you, and I think in a way, I always wanted to do a more straight-ahead horror, although ‘Last Night In Soho’ isn’t quite straight-horror.

BB: Yeah, it’s thriller/horror, it’s a little bit of a mix, but I do think it takes a harder turn into horror at one point than I thought it was going to

EW: Good! I think films should be surprising. I never have any worries about films starting as one thing and ending as another — to me, that’s the joy of going on the journey. Obviously, my first breakthrough movie was ‘Shaun of the Dead’, which had horror elements to it, and I think I’d always liked the idea of doing something that was a bit more serious and darker. But in a way, the build-up to that — and I’ve been thinking about Last Night In Soho for like a decade — was if you’re thinking about something which is disturbing to you, you want to do it right because I don’t know why you would make a horror film if you’re doing about a subject that didn’t scare you in the slightest. So I think part of the gestation period of this movie was building up to it, essentially.

Last Night In Soho and the dangers of nostalgia

Getty Image

BB: Let me ask you then, based on what you just said, what is it that you’re scared of that you’re trying to speak on? My reading of it is that one of the big themes is the dangers of both nostalgia and escapism. You were saying that if it doesn’t scare you, then what’s the point, so what in this film is that for you?

EW: I think there’s a number of elements in this film — the nostalgia thing is a part of it in the sense that I started to wonder why I was so nostalgic, and I am certainly one of those people that would think about, “Ah, wouldn’t it be great to go back to the 60s?” I was born in 1974, so the 60s was the decade before me, and it’s a source of obsession because it’s like you *just* missed it. And then as you start to think about the idea of going back, that is itself a failure to deal with the present day. Are you in retreat because you’re being so nostalgic? On top of that, it’s the idea that it’s a danger of romanticizing the past — the idea of people using the phrase “the good old days” is always questionable because there is no decade where everything was great and nothing was bad. And of course, everything that’s bad now was just as bad in the 60s, and probably in a lot of cases, worse. That was the nightmare of it: that you get to go back and that’s the dream come true aspect, but you can’t have the good without the bad, so I guess it’s like a cautionary tale for time travelers.

And then the other thing that I find nightmarish about it is even though the main character Eloise goes back to the 60s in her dreams, she’s powerless to avert future events, and that to me is the real nightmare because she’s not Marty McFly, she can’t go back and change the future. She basically is powerless to do anything but watch what’s happening and observe and cannot avert an oncoming disaster. And that, to me, is where something is nightmarish: at that point in the movie, once Eloise is on the roller coaster of going back every time she goes to sleep, it’s impossible for her to stop it. I think about reading about true crimes and the idea that you could go back and save somebody is such a weird thing to obsess about — the idea that maybe if you were there, you could stop some terrible tragedy from occurring but, of course, you can’t. So I think there was a thing in the way of trying to cure that within myself, and this idea of to stop fantasizing about going back in time and trying to change your own mistakes and also save people or avert disaster. It’s just an interesting thing to me that occupies my thoughts a lot.

How Last Night In Soho was born

BB: You actually touch on what I want to ask you about: how did this idea come to you? Was there any particular inspiration or moment from your life, whether it be passed to present?

EW: Honestly, aside from the genre influences, the real inspiration is just being in London. I’ve lived in London for 27 years, and London — and then Soho itself, which is a square mile right in the center of London between the West End and Oxford Street, which for centuries has been known as like a den of inequity in terms of where it seems like other rules don’t quite apply to Soho — is a strange place because it’s the center of the film and TV industry and the heart of show business itself, and yet it’s also the heart of the darker side of London. Not so much now where it’s been gentrified like a lot of cities, but there’s still that kind of dark energy to the place, and it’s certainly a place that after midnight, it feels like the old Soho starts to rise up, and as such, as a sort of a nightlife district, it’s both compelling and disturbing in equal measure. And the buildings are all hundreds of years old, they’ve been there for like four centuries, so you can’t stop thinking about it.

BB: The past is literally all around you.

EW: Yes. I’m the kind of person, much like Eloise in the movie, that thinks a lot about what walls have seen and what has been left behind by the previous inhabitants or previous events. And there are two theories about ghosts: the idea that ghosts are souls that are left on Earth in purgatory with unfinished business and are unable to even go to heaven because they haven’t even been found yet — their murder is unsolved or there’s some kind of unfinished business. And then the other theory is the idea that an event would leave something behind, and I think a lot of people believe that, and I would believe that as well, even though I have no proof of it, that if a murder happened in a room, is there any energy left behind by that event? I would say yes.

If you could live during any time period, when is it?

BB: That’s why people legitimately want to know if somebody died in the house before they buy it, that’s a very real thing. Based on what you’ve said so far, I think I know what you’re gonna say now. Ellie actually touches on something that I actually think about a lot: if you could live at any time, when would it be? Now, I usually jokingly say being a pirate because something about the lifestyle just seems like it’d be a blast, except for when, you know, you’re dying of some horrible disease on a wooden ship in the middle of the ocean. So my real answer — and it’s actually related to yours, I was born in 1993 and I’m from New York — is New York City in the 80s with all that excess and booming Americana. What time period or place would you like to live in?

EW: I feel weird saying the 60s in London, because I just made a film about how you shouldn’t go back, but armed with the knowledge of all of the things to avoid, maybe I still would probably go back to 60s London. I have this trove of research that I did for the movie, detailing all of the bad stuff, so if I was smart enough to keep my wits about me. The reason that people obsess about 60s London is that it was a moment where the country was at the forefront of culture, music, just everything. That mid-60s boom. My second option would be 30s Hollywood. That would be an amazing time, but also not without its darkness! You could probably make exactly the same film as Last Night In Soho, but in 30s Hollywood, and not have to change much apart from the scene headings

1930s Hollywood

BB: Based on that, I take it you’re looking forward to Damian Chazelle’s Babylon, then.

EW: Yeah, absolutely — I read a lot about that period and I find it fascinating. I love film history books about that period and about directors from that period, as well. I am so obsessed with Busby Berkeley and how they made those films, which certainly seems like the making of those musicals would not pass muster in terms of the working conditions. But I am looking forward to Damian’s film because it’s an interesting period where, again, Hollywood was slightly a law unto itself because it’s like a new city and it had just been created out of that industry. The reason that everybody went to Los Angeles was just that it had consistent weather. There’s no other reason to build a city in the desert, other than the filmmakers’ thought… obviously, if you’re filming in London or New York, the weather is very changeable, but in L.A., it’s just sunshine all year round, so that’s why they created Hollywood, essentially, in the desert.

The challenges of making a period piece

Focus Features

BB: Correct me if I’m wrong, but I think this is the first of your films that takes place in a time period that’s not the current day. What were some of the unexpected challenges and rewards of that?

EW: Yeah, I mean half takes place in the 60s. The biggest challenge of production, by far, was shooting in Soho, which is genuinely 24/7, so that’s quite challenging. And then on top of that, we were turning some streets into the 60s, in the middle of one of the busiest nightlife districts in London. It was just “I’m taking the bull by the horns and going for it.” We had an amazing location manage and we knew exactly what we wanted to do and we’re just willing to go for it. That was was easily the biggest challenge of the production in that sense, of shooting in an area that people don’t really shoot in.

BB: Right, like trying to film in Times Square.

EW: Yeah! Weirdly, when I watched the film ‘Birdman’, I was really impressed that they had some Times Square scenes, thinking “Wow, that’s not easy to do.” You’re making this film right in the middle of New York.

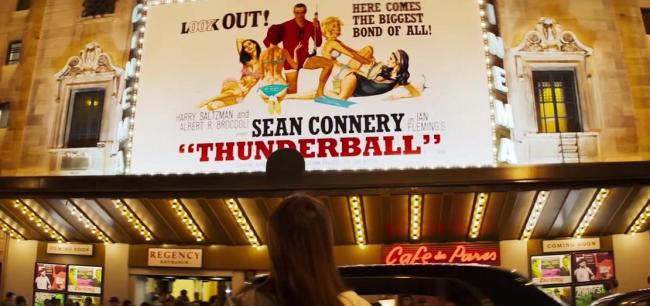

BB: Let me say that your romantic feelings for Soho definitely come through. I believe the shot is in the trailers, Ellie’s first night there, when she walks out to the Thunderball marquee, even I wanted to live there! I don’t blame you, it looked gorgeous.

Edgar Wright’s famed needle drops

BB: This movie begins with a literal needle drop, something you’re obviously known quite well for. What is the process of your films’ music look like? Do you have a list of songs going in? Does it come to you while you’re cutting the film together? Or is it a bit of both?

EW: No, it all comes before. It’s very, very rare where a song is added in past, because usually the songs have been timed. In this movie, there are literal dance sequences to specific songs or references to the songs that are actually playing. There were maybe one or two songs that were added in postproduction because we had room for it. But even those songs come from a big list of songs from the preparation to write this film and in the 10 years it was gestating in my head.

The thing that would keep me inspired to make it would be this slowly growing list of songs, so I’d have a playlist on my iTunes, at first it was called “Soho”, which was like 600 songs, and then it was called “Soho 5 Stars”, and it was 300 songs. And then, from that, the ones rise to the top in terms of “I know that this is a song that I want in the movie.” Or, in some cases, there would be a song where I would visualize the scene as I was listening to it. The first 60s dance number is set to a cover of a song by The Graham Bond Organisation called “Wade in the Water.” And I would hear this particular cover and I was like, “I’ve got to use this in the film,” and then I would just see the scene in my head, I knew what it was. It’s almost like a movie version of synesthesia, the condition where you see colors and link them to music. I guess I have the movie version of synesthesia.

Casting Thomasin Mackenzie and Anya Taylor-Joy

BB: It sounds like a hell of a tool to have in the bag. Let’s talk about your two leads: was there ever a world where they switched roles? How did you go about finding the right person for the right part? Because I would say Thomasin and Anya — while Anya is a bit older — they’re both at similar stages of their careers, they both have the same immense talent, so how did the casting process go for you?

EW: Anya Taylor-Joy was the first person I met about the film, maybe like three years before we even had the script. Because at Sundance in ‘The Witch’. I was on the jury, actually, that gave Robert Eggers Best Director, so I had seen that movie, and even as I was watching that, I was saying to myself, “She should be the lead of my Soho film.” Then I met her for coffee in Los Angeles shortly afterward and I ended up telling her the entire plot of the movie. I’m not sure I planned to tell her the whole plot, it just kind of happened, and then she was like, “Wow, okay,” she goes, “I wanna be in that film.” And then I say, “Well, as soon I’ve got a script, I’ll get it to you,” and then I went off and made ‘Baby Driver’ for the next three years. And I had seen Anya a couple of times and I kept in touch with her, but I’m sure it started to feel like the Boy Who Cried Wolf about this script that didn’t exist.

Eventually, in 2018 when me and Krysty Wilson-Cairns were writing the screenplay, by this point I’d seen Anya in a number of other movies like ‘Split’ and ‘Thoroughbreds’, and I started think, “Oh, maybe she’s already done the Eloise part in a way, or she’s gone beyond there,” and at that same time, the Sandy part in the script was getting bigger and expanding in the draft, so it occurred to me, having seen Anya in other movies and on red carpets and fashion shoots…

BB: She’s got that classic look to her, absolutely.

EW: I just thought she should play in the 60s part. And then when I sent her the script, I was a bit nervous that she might react badly to it, but I said, “Hey, here’s the script, will you look at the part of Sandy instead of Eloise?” And luckily she emailed back and said “I’d love to be a part of the movie and I’d love to play Sandy.” So she was the first person attached to play Sandy, and then after that, we went looking for Eloise and Thomasin Mackenzie’s name was one of the first people mentioned by my producer. I had seen her in that film ‘Leave No Trace’, directed by Debra Granik, which was incredible. It’s also worth pointing out, in the movie was 18 years old and playing an 18-year-old. That doesn’t always happen. In a strange way, Thomasin coming to London to make the movie, and Eloise coming to London *in* the movie, is inextricably linked in my head forever.

Working with rising talent

Focus Features

BB: And on the stars — and not to cast aspersions on their careers — but I would say that most your films don’t star a bonafide A-lister, but someone on the verge of it. And this is obviously the case with Anya and Thomasin, both of which are being pegged by a lot of people to be the next big thing. Is giving talent you believe in a career boost something that you seek out to do? Or has it just happened to be this way? I mean, you’ve caught Anya Taylor-Joy during *her moment*. Is that by design?

EW: Not by design in the sense that she shot ‘The Queen’s Gambit ‘immediately after we did ‘Last Night In Soho’. We had to go on hiatus because of the lockdown, so actually, she came back after ‘The Queen’s Gambit’ to do some additional filming. The thing with Anya is, in my head, I already thought she a megastar. There’s that kind of thing where people like that talented like Thomasin and Anya, you’re waiting for the rest of the world to catch up. I certainly had that feeling with people that I cast in Scott Pilgrim, as well — I thought they were going to be huge. I remember even saying to Donna Langley at Universal, “Brie Larson is going to be enormous!” And she was 19 when I cast her in ‘Scott Pilgrim’. But it’s not really by design. I like casting actors who are close to the age of their part, so maybe that has something to do with it. Whether it’s in ‘Scott Pilgrim’ or ‘Baby Driver’ or in this, casting actors that are close to the age of the parts just gives it some kind of verisimilitude that’s different if you were casting a 26-year-old pretending to be an 18-year-old, it’s simple as that. So, by that nature, you tend to cast up-and-comers.

Crafting a thrilling twist

BB: We don’t need to go into the details, but I want to ask you about the film’s twist and just writing twists at large. At what stage of the writing do you come up with twists? Is it something that you work backward from? Or is it something that you arrive at?

EW: I would say it’s something that you work backward from, as in I knew what the ending of the movie was very early on in terms of the story. So when you’re writing it, you’re leading up to that. I don’t really want to talk too much more about it because, in a weird way, some people go in not knowing that there is going to be a twist at all.

It’s a tricky one [writing twists]. I feel like people are unnecessarily tough on M. Night Shyamalan, because they sort of say, ‘Oh, it’s all about the twist!’ And, it’s like… why not? I don’t care if that’s his thing, I enjoy it. I actually thought the twist in ‘Old’ was actually really good, I liked it. I thought the final five minutes was like, ‘Yeah, I’m in! I’m in, man.’ I like films that give you something like that, and I particularly like films that, sometimes you get it in old thrillers from the 60s and 70s, where it seems like the film is over, and you go, ‘Huh, I guess it’s done,’ but then there’s an ‘and then…’, and then the finale kicks in. I like the fact that you think it’s done and then something else is coming. Dressed To Kill has a good one like that: where it feels like the film is done and then that’s an extra 15-minute operatic set piece at the end.

BB: I don’t know if you’ve ever seen Primal Fear with Edward Norton. That’s a great example of that.

EW: Oh yeah, of course.

Remakes, reboots, sequels, and spinoffs

BB: Let’s loop back to escapism and nostalgia: do you feel like these two things are becoming increasingly relevant or relied upon these days, and what are you trying to say about that in this film?

EW: I’m 47 years old, and I’m not so enamored with 80s nostalgia because I grew up in the 80s. I understand why other people get interested in it, but I don’t really need to see the same ten movies being remade for the rest of my life. In cases where people are remaking films, I think if you’re making a film for your kids, I understand that in terms of “This was a big film to me when I was a kid, and I’d like to make a version of it for my kids.” I understand that. But when you’re just recycling the same ten franchises *just because*, it’s starting to wear on me because I’ve already seen the first version of that film in 1979. I don’t want to mention any names for any films because I know these filmmakers, but there was one in particular — and I won’t even say it because I know the people making the new one — but it’s like, honestly, I could just take the first one and if you could delete all the sequels, I would do it in a heartbeat. You don’t need anything more than the original film, and there are so many of them that are like that, where remakes are just reminding you of how you felt about the first one. Sometimes, somebody makes a sequel where it’s additive. James Cameron’s ‘Aliens’ is additive to the franchise, because the first one is great, and then the second one is great, and it’s doing something different at the same time. But I think too many times recently people are just trying to conjure up the feeling of seeing the first film.

Franchise filmmaking is not going to go away and I just wish people would take more risks. But that’s also difficult because then — I’ve seen it happen to friends of mine who’ve made franchise movies, and it seems like you’re really just caught in a no-win situation — if you do something that’s exactly like one of the original ones, people just say it’s like karaoke, and if you do something bold and different, some members of the fanbase just start like committing Harakiri. And you really think, “Everybody calm down, it’s just a movie.” I actually managed to get through that without mentioning a single film or filmmaker! I’m very happy about that.

Franchise filmmaking and James Bond

Getty Image

BB: You did tee me up on something that I want to ask about: IP and franchising and all that. And I want to ask you about Ant-Man, but not in the way that you expect. It’s already been over half a decade since that film, and the reliance on IP and franchising has only grown since then and will continue to do so. What is it like navigating this current landscape as a director, particularly one who is so celebratedly unique as yourself, and does it inspire you to be even more your own artist?

EW: I would never be so dumb to say that I’d never do a franchise movie. I’ve said that on record, it’s not like I ever said I’d never do one. And when it’s announced in some trade magazine that I am doing one, everyone will say ‘Edgar, you lied! You said you’d never do a franchise movie!’ I never said that. The thing is, I really believe that studios have to make more original films. And I don’t mean original standalone films, but even original films that could become franchises.

BB: Like John Wick?

EW: Yeah, that’s a good example of a recent one, for sure. What’s strange to me is that there seems to be this shortsightedness that nobody seems to understand that in 1977, ‘Star Wars’ was an original screenplay, or that in 1979, ‘Alien’ was an original screenplay, or that in 1984, ‘The Terminator’ was an original screenplay. So, it’s like, why wouldn’t you take more risks on things that *could* go beyond? I’ve been a film fan since I was three years old, but I think if I could go back to the 80s’ me and say, Hey! Guess what?! All these films that you love, they’re gonna be making them forever!’ I think I’d be pretty bummed out even then. I just don’t feel like I need to just keep seeing the same thing.

It’s fine when there’s a great reinvention of something. And when people do reinvent a franchise — like when the first Daniel Craig Bond came out — they’re doing something radically different as a reboot, it’s very interesting to watch. And that I think is fair and was a great example of that. Some of these things could take a break. And it’s not like they don’t need to come back, but I don’t need one every two years.

BB: I guess you’re saying that we could get the Edgar-Wright-to-direct-the-next-Bond-film train going now, huh?

EW: I didn’t say that! But I will say — and I did say this to [‘No Time To Die’ director] Cary Fukunaga, who’s a friend of mine — that bizarrely there are two films in October that feature the 007 logo. At the end of Last Night In Soho, because we used the ‘Thunderball’ marquee — Barbara Broccoli and Michael G. Wilson gave us permission to use it — I actually got in touch them saying, ‘Hey, I’m coming to you with a Bond-related request that has nothing to do with your film!’ If you look in the end credits, the 007 logo is in there because it says “Property of Eon” and everything. There are a few Bond references in Last Night In Soho beyond the marquee, too. They drink vespers, and Diana Rigg is also a Bond alumni. Margaret Nolan, who has a cameo in the movie, is also a Bond alumni.

BB: Edgar, I’ve gotta wrap here, it was an absolute honor and thrill to talk to you. I wish you all the best with Last Night In Soho — it’s a fantastic, devilishly fun movie. It hits theaters on October 29th, and I can’t wait to see what you do next. Sir, take care.

EW: Thank you very much.

Subscribe and listen to our pop culture podcast, the Post-Credit Podcast, and follow us on Twitter @PostCredPod

(Apple | Spotify | Google Podcasts | Stitcher | Anchor)